Cleveland, OH (CLE)

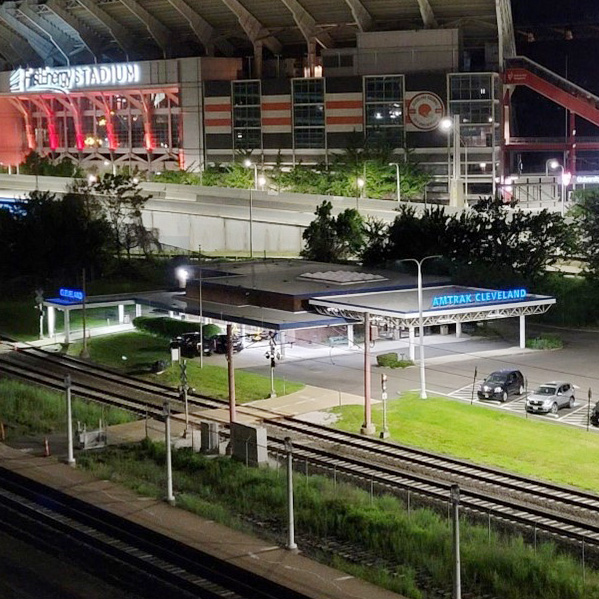

Lakefront Station sits in good company among waterfront attractions such as the Cleveland Browns Stadium, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Great Lakes Science Center.

200 Cleveland Memorial Shoreway

Cleveland, OH 44114

Annual Station Ridership (FY 2024): 58,930

- Facility Ownership: City of Cleveland

- Parking Lot Ownership: City of Cleveland

- Platform Ownership: Norfolk Southern Railway

- Track Ownership: Norfolk Southern Railway

Ismael Cuevas

Regional Contact

governmentaffairschi@amtrak.com

For information about Amtrak fares and schedules, please visit Amtrak.com or call 1-800-USA-RAIL (1-800-872-7245).

Amtrak trains glide along the shore of Lake Erie before making their early morning stops at Cleveland’s Lakefront Station north of downtown. From 1971-1972, Amtrak served Cleveland Union Terminal on Public Square in downtown Cleveland. Due to the large size of the facility and the requirement for operators to switch to electric locomotives in order to access the enclosed platforms, Amtrak decided to construct a smaller station that could better accommodate passengers and serve its needs. The new depot opened in 1977 and today sits in good company among waterfront attractions such as the Cleveland Browns Stadium, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, and the Great Lakes Science Center.

Lakefront Station is a one-story reddish-brown structure constructed of concrete masonry units. A large and prominent porte-cochère protects passengers arriving by car from rain and snow and allows them to pull right up to the entrance. Typical of 1970s design aesthetics, the trussed support system of the porte-cochère is exposed for all to see. Whereas pre-Modern architects would have hidden this portion of the structure, many Modernists celebrated the functional aspects of their buildings. These architects wanted people who were interacting with their structures to understand how they were assembled, and thus essential components of systems like heating and air-conditioning, water, and electrical were left showing. From the porte-cochère, a covered walkway wraps around the corner to the trackside façade and eventually leads to both the Amtrak and local light rail platforms. Trimmed in a vibrant, deep blue, the covered walkway provides a welcome contrast to the subdued tones of the brown walls.

The materials used on the exterior continue into the interior. As sunlight streams down through a central skylight, it hits the exposed trusses that support the roof and throws interesting patterns onto the brown brick floor, which is laid in a basket weave pattern. Exposed ductwork snakes its way through the trusses as do the light fixtures. Since all the ceiling elements are painted white, they tend to recede and produce a sense of airiness which is further enhanced by the floor-to-ceiling windows. Banks of seats are located close to public telephones and a vending area.

As one of the premier ports on the Great Lakes and one of Ohio’s largest cities, over the years Cleveland has supported a handful of stations served by numerous rail lines. It also boasted dozens of other railroad-related structures such as freight houses, round houses, crew quarters, and repair shops, most of which are now gone as technology changed and railroad mergers resulted in redundant properties.

Located where the Cuyahoga River empties its waters into Lake Erie, Cleveland was founded in 1796 and named for General Moses Cleaveland. Before Ohio existed, the land south of Lake Erie—referred to as the “Western Reserve”—belonged to Connecticut, as many of the original thirteen colonies theoretically spanned the continent from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. Cleaveland was a shareholder in the Connecticut Land Company which had formed in the late eighteenth century to promote settlement in the Western Reserve. He was appointed by the other stockholders to supervise the surveying of the land, a necessary step in its settlement. The capital city of the Western Reserve was placed at the site of Cleveland and the surveyors named it after their leader. The general laid out the basic street plan which included the ten acre Public Square modeled after New England town greens. Once surveying was complete, Cleaveland went back to Connecticut and never returned to the Northwest Territories.

Early settlers developed the harbor to take advantage of Great Lakes trade. Canal building fever excited the new nation in the 1820s and 1830s, and Ohio was not to be left out. By 1827, the Ohio and Erie Canal connected Cleveland with Akron forty miles to the southeast and eventually was completed to the Ohio River. The canal gave farmers in the state’s interior access to new markets through the port of Cleveland, and further enhanced the lakeshore city’s economic well-being.

Entrepreneurs recognized the increased trade benefits that came from the canal and some began to look to other transportation modes that could improve upon canal shipping. Ohio businessmen clamored for rail connections to the east coast and the nation’s primary population centers and international port cities. In March 1845 the original 1836 charter of the Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati Railroad was renewed by the state legislature, and the company was authorized to build a line from Cleveland to the state capital at Columbus; from there it could then build south to the Ohio River. After six years of grading and construction, the railroad linked the two cities and in February 1851 a celebration train carrying members of the state legislature and prominent citizens made the trip from Columbus to Cleveland where they were greeted by “discharges of artillery, and the welcome of thousands of our citizens.” The day continued with a speech given by the mayor on Public Square and later a banquet.

Cleveland’s first Union Depot was along the lakefront at the northern edge of 9th Street, not far from the current Amtrak station. Described as a brick structure beside a collection of wood sheds, accounts tell how it partially burned in 1864. The fire prompted the construction of a large masonry structure to the west between 6th and 9th Streets and passenger services were transferred to this “new” Union Depot while the remaining parts of the “old” station were used for the cleaning, repair, and housing of cars. Constructed at a cost of $475,000, new Union Depot was essentially a large train shed with walls built of regional Berea sandstone. Measuring 603 x 180 feet, it incorporated structural iron and was considered one of the largest roof spans in the country. Like many stations built at the time, it had a prominent 96 foot tall tower with clock faces.

As the rail lines grew in every direction, Cleveland found itself to be in a favorable geographic position. The city was right in the middle of the natural resources that gave rise to iron and steel, essential industrial products that helped usher in the modern age. Coal from western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio was brought by rail while iron ore from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and Minnesota made its way south by ship. In fact, the other major railroad company chartered by the state in 1836 was authorized to build a line from Cleveland to Ohio’s eastern border where it could then connect with a line built through Pennsylvania coal country. Iron and steel manufacturing became major industries in Cleveland as in a number of cities and towns along the Great Lakes; the Civil War would provide a major boost to the fledgling sectors.

In 1870, John D. Rockefeller founded Standard Oil in Cleveland although its headquarters later moved to New York City. Cleveland was a wise starting point, as the United States’ first oil wells were located nearby in northwestern Pennsylvania. Standard Oil quickly outwitted its competition and dominated the oil refining and distribution market, eventually becoming an early multi-national corporation. With an emphasis on steel and oil, Cleveland became a natural center for the automobile industry and nurtured companies such as White and Gaeth, Peerless, and Baker, which respectively produced steam, gasoline, and electric cars. Chemical industries rose in prominence also, and paint, varnish, and enamel manufacturers such as Sherwin-Williams and Glidden were organized in the city. The industrial infrastructure of the city was so impressive that tour books such as Baedeker’s suggested a visit to the city’s “Oil District”—where Standard Oil had its refinery and storage tanks—and the ore docks on the west side of the river.

A major Midwestern city, Cleveland’s civic leaders began to reconsider the metropolis’ image and in the first decade of the century, famed architect and planner Daniel Burnham and associates were chosen to help redesign the core of the city. Much like similar “City Beautiful” efforts in Washington, DC, Chicago, and San Francisco, the design team envisioned a formal axis or landscaped “Mall” leading from downtown to the shores of Lake Erie where a new train station would be built. The great “outdoor room” of the mall would be bordered by neoclassical buildings housing the city’s important institutions and government agencies.

While the 1903 “Group Plan” was never fully completed, many of its elements were carried out, including the new train station. New Union Depot had grown too small and years of accumulated soot and ash had made the building into a dirty eyesore. Instead of placing the proposed terminal at the end of the Mall axis on the lake, thirty years later it eventually ended up on Public Square. This move was the work of brothers Oris Paxton and Mantis James Van Sweringen, real estate developers who had created one of America’s first garden suburbs at Shaker Heights east of downtown Cleveland. Needing a way to get residents to the city center, the brothers purchased the Nickel Plate Railroad in 1916 in order to obtain the right-of-way into Cleveland. Within another decade, the brothers owned 30,000 miles of railroad and held stakes in steel, rubber, and automobile companies. With their great business acumen and seemingly “golden touch,” the Van Sweringens proposed a new terminal complex on the southwest corner of Public Square.

The Van Sweringens did not plan to build just a station, but rather a complex of modern office buildings that became a “city within a city” that included seven buildings over fifteen acres. The group of buildings was particularly novel because it took advantage of air rights over the railroad tracks; streets and buildings would rise over the tracks, hiding the activity of the railroad from public sight and creating a new landscape in one of the oldest parts of Cleveland. This vision required the assemblage of hundreds of parcels, a legal feat in itself. In addition to the buildings, miles of grade separated rail right-of-way were dug and the lines were electrified. The Van Sweringens hired the Chicago firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White—successors to the firm of Daniel Burnham—to design the complex which cost $179,000,000.

In keeping with the Burnham “Group Plan,” the Terminal complex was sheathed in a streamlined Neo-classical architectural language that provided visual unity to the buildings and gave them the appropriate sense of grandeur. The centerpiece Terminal Tower grew from a conceptual 14 story structure to a 52 story skyscraper that was North America’s second tallest building when completed. It was the tallest building in the United States outside of New York’s skyscrapers until 1967. Modeled after the Manhattan Municipal Building, it features an arcade with seven three-story arches at the base opening onto Public Square and a distinctive setback topped by a cupola. Dressed in grey limestone attached to a steel skeleton, the main tower is flanked by two smaller twelve-story buildings that originally housed a department store and hotel. Movie fans might recognize the former Higbee’s department store building—now the Positively Cleveland Convention and Visitor’s Bureau—as the place where Ralphie goes to see Santa Claus about his Christmas wish in A Christmas Story.

In 1922, clearing of the site began, and more than one thousand structures had to be razed and three million cubic yards of material removed. The official groundbreaking took place in 1923 and the erection of the steel skeleton began in 1926. The Terminal Tower opened to the public in June 1930, and the observation deck on the forty-second floor was an especially popular destination.

The railroad station was built by the New York Central, Big Four, and Nickel Plate Railroads, and was also used by the Van Sweringens’ rapid transit line to Shaker Heights; the Baltimore and Ohio and Erie Railroads later moved into the terminal while the Pennsylvania Railroad remained at Union Depot until 1953—it was then demolished in 1959.

Rail passengers coming from Public Square entered the grand arcade with its giant windows and coffered ceiling and descended ramps down to the concourse which featured a large skylight that flooded the area with natural light. Floors of Tennessee pink marble, walls of beige Botticino marble laid in coursed ashlar, and lighting fixtures and hardware of brass and bronze awed passengers and impressed visitors with the power of the railroads. The concourse later received a colorful mural painted on porcelain panels made locally by the Ferro Enameling Corporation. Designed by John Williams Scott and painted by local artist Daniel Boza, the 28×73 foot mural was made for the Transportation Building at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. In stunning colors, it depicts riders on horseback and allegorical angels. In 1941, it was transferred to the Terminal Tower where the phrase “Welcome to Cleveland” was added below it in metal letters.

The well-regarded Harvey Company ran the concessions which included sit-down restaurants, cafes, tearoom and a sandwich shop which all together could serve about 10,000 customers at lunch. While waiting for trains, travelers could browse in the Harvey-run bookshop, toy store, drugstore, or perhaps run to the barbershop for a trim. Hidden from view were the working areas of the railroads such as the baggage rooms, crew bunkroom, mail facilities, and the coach yard.

As transportation modes and choices increased and train travel lost a share of the transportation market, the Terminal Tower station fell out of use and by 1977 was only served by local rail lines. In the 1980s, the Terminal Tower complex was renovated and much of the concourse was demolished to build a new shopping mall known as Tower City Center that has shops, restaurants, and a movie theater. The Ferro Mural was moved to the Western Reserve Historical Society Museum.

The Terminal Tower is an unofficial symbol of Cleveland, and a guiding beacon for visitors who come to enjoy the diverse sights and neighborhoods of this lakeside city. As a major inland port, Cleveland received large numbers of immigrants in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, particularly from Germany, Italy, Russia, and Eastern Europe. Traditions from these heritage nations and the birthplaces of more recent immigrants from Asia and Central America are present in the West Side Market, the city’s oldest operating market space. The present building dates to 1912 and includes more than 185 stalls inside the building and under the outdoor arcades. Hungry patrons can find just about any cuisine they desire, or the fresh produce and goods needed to cook a favorite meal.

Devotees of the theater make their way to PlayhouseSquare between downtown and Cleveland State University. Considered the nation’s largest performing arts center outside of New York City, this stretch of Euclid Avenue boasts eight theaters within a few blocks of one another. Most of the theaters were built in the 1920s but had closed by the 1960s only to undergo restoration and rejuvenation in the late 1970s and 1980s. Broadway shows, concerts, opera, dance programs—everything can be found at PlayhouseSquare. The consortium of theaters is noted for its “Partners in Performance” education program. It exposes children to the performing arts by subsidizing performances and transportation to the venues.

“Severance Hall”—words of joy to a classical music lover. The acclaimed Cleveland Orchestra has played at this grand concert hall for over eight decades. Although the building displays a refined neo-Georgian façade, the interior mix of Egyptian, Greek, and Roman motifs is considered a highpoint of American Art Deco design. The theater stands in good company in University Circle, a neighborhood five miles east of downtown that is home to numerous museums and Case Western Reserve University which is known for its medical school and biomedical research facilities. Nearby stands the Cleveland Clinic, considered one of the best hospital systems in the world with more than 120 medical specialties. The Clinic is currently the city’s largest employer, and is the anchor of a growing biotechnology and high-tech industry that takes advantage of the city’s institutions of higher learning.

Station Building (with waiting room)

Features

- ATM not available

- No elevator

- No payphones

- No Quik-Trak kiosks

- Restrooms

- Ticket sales office

- Unaccompanied child travel allowed

- No vending machines

- No WiFi

- Arrive at least 45 minutes prior to departure if you're checking baggage or need ticketing/passenger assistance

- Arrive at least 30 minutes prior to departure if you're not checking baggage or don't need assistance

Baggage

- Amtrak Express shipping not available

- Checked baggage service available

- Checked baggage storage available

- Bike boxes for sale

- Baggage carts available

- Ski bags for sale

- Bag storage

- Shipping Boxes for sale

- Baggage assistance provided by Station Staff

Parking

- Same-day parking is available; fees may apply

- Overnight parking is available; fees may apply

Accessibility

- No payphones

- Accessible platform

- Accessible restrooms

- No accessible ticket office

- Accessible waiting room

- Accessible water fountain

- Same-day, accessible parking is available; fees may apply

- Overnight, accessible parking is available; fees may apply

- No high platform

- Wheelchair available

- Wheelchair lift available

Hours

Station Waiting Room Hours

| Mon | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Tue | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Wed | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Thu | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Fri | 12:00 am - 02:30 pm |

| Sat | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Sun | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

Ticket Office Hours

| Mon | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Tue | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Wed | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Thu | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Fri | 12:00 am - 02:30 pm |

| Sat | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Sun | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

Passenger Assistance Hours

| Mon | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Tue | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Wed | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Thu | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Fri | 12:00 am - 02:30 pm |

| Sat | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Sun | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

Checked Baggage Service

| Mon | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Tue | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Wed | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Thu | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Fri | 12:00 am - 02:30 pm |

| Sat | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Sun | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

Parking Hours

| Mon | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Tue | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Wed | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Thu | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Fri | 12:00 am - 02:30 pm |

| Sat | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

| Sun | 12:00 am - 07:30 am |

Quik-Track Kiosk Hours

Lounge Hours

Amtrak Express Hours

| Mon | CLOSED |

| Tue | CLOSED |

| Wed | CLOSED |

| Thu | CLOSED |

| Fri | CLOSED |

| Sat | CLOSED |

| Sun | CLOSED |

Amtrak established the Great American Stations Project in 2006 to educate communities on the benefits of redeveloping train stations, offer tools to community leaders to preserve their stations, and provide the appropriate Amtrak resources.

Amtrak established the Great American Stations Project in 2006 to educate communities on the benefits of redeveloping train stations, offer tools to community leaders to preserve their stations, and provide the appropriate Amtrak resources. For more than 50 years, Amtrak has connected America and modernized train travel. Offering a safe, environmentally efficient way to reach more than 500 destinations across 46 states and parts of Canada, Amtrak provides travelers with an experience that sets a new standard. Book travel, check train status, access your eTicket and more through the

For more than 50 years, Amtrak has connected America and modernized train travel. Offering a safe, environmentally efficient way to reach more than 500 destinations across 46 states and parts of Canada, Amtrak provides travelers with an experience that sets a new standard. Book travel, check train status, access your eTicket and more through the