Brattleboro, VT (BRA)

The former Union Station was built into a bluff along the Connecticut River. The waiting room occupies the ground floor, while the upper levels have been converted for use as an art museum.

10 Vernon Road

Brattleboro, VT 05301-3389

Annual Station Ridership (FY 2024): 16,845

- Facility Ownership: Town of Brattleboro

- Parking Lot Ownership: Town of Brattleboro

- Platform Ownership: New England Central Railroad

- Track Ownership: New England Central Railroad

Jane Brophy

Regional Contact

governmentaffairsnyc@amtrak.com

For information about Amtrak fares and schedules, please visit Amtrak.com or call 1-800-USA-RAIL (1-800-872-7245).

Nestled amid the hills of the upper Connecticut River Valley, Brattleboro is the principal city of southeastern Vermont. Just across the river lies New Hampshire while the border with Massachusetts is only about 10 miles to the south. The Amtrak station is located at the southern end of Main Street, which runs up to the town common and is lined with historic buildings dating to the 19th and early 20th centuries.

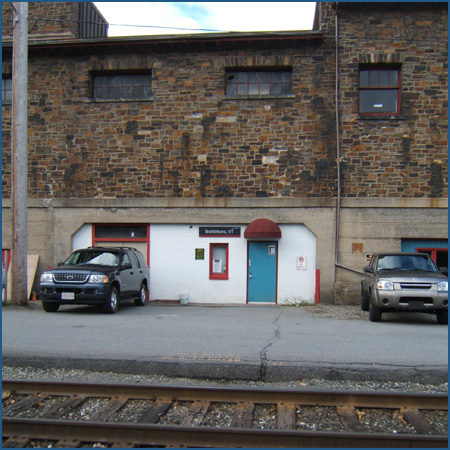

The Amtrak passenger waiting room occupies the ground floor of the former Brattleboro Union Station. The two other levels are home to an art museum. To address the town’s varied and dramatic topography, the architects built the station into a high bluff. Therefore, the main entrance, now used by the museum, is on the third floor and faces Vernon Street while the Amtrak entrance is on the ground floor and is accessed via Bridge Street.

The railroads chose this site on the west side of the tracks along a bluff. Completed in 1915 for $75,000, Union Station is composed of quartzite stone laid in a rustic random rubble design that emphasizes its hand crafted construction. The stone was quarried from Wantastiquet Mountain, looming over the city from the New Hampshire side of the river. From north to south, the station consists of the main passenger building, a recessed baggage wing, and a freight building.

The center of the passenger building, which is five bays across, is marked by a projecting pavilion topped by a gable that contains a stone plaque inscribed with “1915.” The base of the pavilion contains three doors through which passengers entered the station, sheltered by a metal and glass marquee. Passing through the waiting room, travelers accessed the southbound platform down a set of stairs; a bridge was used to cross the right-of-way and reach the northbound tracks. On the middle floor of the passenger building, an oriel window was strategically placed so that the train dispatcher and the telegrapher could view and monitor traffic along the rails.

The passenger building and baggage room are capped with elegant, hipped slate roofs while the freight building has a flat version with a wide overhang covering the loading dock. It protected goods and workers from rain and snow while items were transferred from the storage area to the waiting trucks; wide doors allowed for the easy movement of large crates and parcels. The freight house was busy, as much of the town’s industrial output passed through its doors.

In June 2024, Amtrak, in conjunction with the town, state of Vermont, Federal Railroad Administration, New England Central Railroad and the Vermont Agency of Transportation, broke ground on a new Brattleboro station and the state’s first-ever level boarding train platform. Customers will no longer require steps to get on or off a train for a more seamless and safer experience due to the new platform sitting four feet above the top of the rail.

Brattleboro is one of the busiest stations in the Green Mountain State, and the new facility will feature an indoor waiting room with fixed seats for 36 passengers and additional standing room, a new accessible single-occupant restroom and a covered, outdoor waiting area with benches. Platform upgrades will include an electric snow melt system, lighting, railings, a detectable warning edge and signage. Additionally, an art installation of the Brattleboro Words Trail, a multi-media, community-produced tribute to the rich literary and cultural history of the area, will be featured on the depot’s track-facing outside wall. The project is primarily funded by the federal Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act.

When European explorers first visited what is now southeastern Vermont, it was primarily inhabited by the Squakheag American Indians who belonged to the larger Abenaki people of the Algonquian language family. Unlike portions of the New England coast, Vermont was difficult to access due to mountain ranges and thick forests. It remained beyond the sphere of most European-American colonists well into the mid-18th century and acted as a buffer zone between the French towns of southern Canada and the English settlements of coastal New England. The region only became attractive to a greater number of English colonists after the British defeated the French in 1760 and gained permanent control of Canada.

Vermont did not come into existence as a separate entity until 1777 because the land was disputed by New York, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. Southeastern Vermont included an area known as the “Equivalent Lands” that Massachusetts had given to Connecticut as settlement in a land dispute. In 1716, Connecticut sold the parcel to a group of 16 investors, among them Colonel William Brattle, who might also have acted as the land agent. Another plot south of present day Brattleboro went to William Drummer, and Massachusetts soon received permission to build and garrison a frontier fort there to protect settlements against incursions by the French and their American Indian allies. Constructed in 1724, the fortification was named after Drummer and became the first European-American settlement in Vermont.

By 1750, the fort was no longer needed, but three years later, the town of Brattleborough—later shortened to Brattleboro by the post office—was chartered to the north along the river on land belonging to Col. Brattle. Similar to many early settlements in the territory, its charter was issued by Governor Benning Wentworth of New Hampshire, further adding to the land disputes among the neighboring colonies.

The location of the town was ideal, for the hills gave protection, the river provided an outlet to more populated areas further south, and Whetstone Brook supplied ample water power for industry. The earliest residents arrived in the 1760s to establish a tavern and basic but essential industries including grist and saw mills that provided vital finished goods such as processed grain and cut wood for building construction. A stagecoach line to Albany passed to the west where another cluster of homes and businesses was established to serve travelers.

Vermont remained an independent republic until 1791 when it joined the United States as the 14th state. Brattleboro was one of its primary cities, and by the beginning of the 19th century could boast of a number of industrial concerns, especially those related to lumber which was found in abundance. The town became known for its paper mills, printing shops, book binders, and furniture makers. Grains, maple sugar, and other agricultural products and finished goods could be shipped down the Connecticut River by flat-bottom boat, or carried overland to large cities such as Boston.

Brattleboro’s bucolic setting also became a place for healing, especially after resident Anna Marsh died in 1834 and left $10,000 to found a new kind of hospital for the mentally ill. Contemporary thought declared the mentally ill to be possessed by demons and treatment included chaining patients to walls and dousing them in water to shock the spirits out. Marsh declared that her hospital should follow the revolutionary Quaker model of “moral treatment” which disabused the notion of demonic influence and instead emphasized healing through work, imaginative activities to stimulate the mind, a healthy diet, and exercise. The clinic, known as the Brattleboro Retreat, was one of the earliest psychiatric facilities in the nation.

Although the river provided an outlet for Brattleboro’s goods, spring flooding and winter icing could disrupt shipping, and therefore merchants and residents began to search for better alternatives, including a railroad to connect it with Boston, greater New England’s principal international port and cultural hub. First discussed in 1836, nothing came of the railroad idea for another decade until the Vermont and Massachusetts Railroad was chartered in 1844. Leased by a succession of other railroads, the line finally came under the control of the Central Vermont Railroad (CV) in the early 1870s.

Arriving on the afternoon of February 20th, 1849, the first train to Brattleboro was met with cheers and shouting, music, and the ringing of church bells. In a children’s poem composed to commemorate the momentous day, local resident Louisa Higginson wrote, “I come! I come! Ye have called me long, / I come through the hills with a clattering throng/ Of cars behind me, which shake the earth/ And to many an uncouth sound give birth.” A band led the passengers and townspeople on a procession up Main Street to the Common after which it returned to the depot for a great feast. The festivities continued with a ball that evening and breakfast the next morning before the train returned to Boston. To accommodate all of the visitors, the doors of the churches were thrown open and party-goers slept on the pews.

The first depot, a long one-storey building with a gabled roof, was built on the banks of the Connecticut River not far from the present site of Union Station. Recent investigations have determined that a wooden structure with two dormer windows that sits near the tracks may be a former freight house that was part of the original station complex. When no longer needed by the railroad, it was turned over to other businesses including a meat company and archery shop.

In 1880, a larger and more substantial two story brick station was built to the south of the first depot. From historic photographs, it appears to have sported a steep gabled roof and a central tower on the trackside façade. Typical of the then popular Queen Anne style of architecture, the gables of the building were decorated with heavy timber stickwork and the tower appears to have been crowned with a wrought iron railing. A train shed with a bowed roof covered a few tracks and sheltered passengers from inclement weather as they waited for the train to arrive. This depot later became a “union station” when the Boston and Maine Railroad (B&M) built a trestle across the Connecticut River to connect with the CV.Through a calculated campaign of acquisition and consolidation, the B&M leased numerous regional short lines and competitors to become the dominant passenger and freight railroad in the far Northeast. The CV and B&M subsequently shared their tracks to separate south and northbound traffic.

During this period, Brattleboro blossomed as an artistic center and produced an astounding number of writers, artists, and architects who went on to long and celebrated careers. William and Richard Morris Hunt respectively dominated the fields of portrait painting and architecture in the last quarter of the 19th century. Hunt designed many of the eclectic-style mansions along New York’s Fifth Avenue that housed America’s Gilded Age magnates.

William Rutherford Mead also entered into the architectural profession; joined by Stanford White and Charles McKim, and created one of the most prolific and sought-after design firms in American history. Their collective output included New York’s Pennsylvania Railroad station and Boston’s Public Library on Copley Square. In Brattleboro, Mead designed the Wells Fountain near the Brooks Memorial Library. British writer Rudyard Kipling married a woman from Brattleboro, and in the early 1890s they lived in a house north of town that they called Naulakha, meaning “precious jewel.” Kipling completed the first part of his famed Jungle Books while living in his custom built retreat.

From the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries, Jacob Estey’s company produced more than 500,000 reed organs that were shipped around the world. After an 1869 flood swept through town, Estey decided to move his factory to a higher elevation, and in time, 14 structures were built. At the height of production, the manufacturer also produced pipe and electronic organs. To house its workers, the company sponsored the residential development of Esteyville.

As federal transportation priorities shifted after World War II to planes and automobiles, many towns, including Brattleboro, lost their passenger rail connections. Union Station closed in September 1966 and was sold to the town. A proposal to raze the building and create a parking lot prompted concerned residents to work with city officials to consider reuse options for the structure. In 1972, it reopened as the home of the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center, a non-profit organization that works to present exhibits by regional, national, and international artists. A year later, Amtrak took over the ground floor for use as a waiting room to serve passengers on the Montrealer, replaced in 1995 by the Vermonter. In recognition of its material integrity and tangible ties to Brattleboro’s extensive rail heritage, the station was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

In the late 1990s, Brattleboro officials proposed a two phase multi-modal project to include a downtown parking garage and a refurbished Amtrak station. The project received $8 million from the Federal Transit Administration; $1.8 million in state grants; $4 million in local funds raised by bond issue; and $1.2 million through other sources. The garage, which also includes a local and intercity bus facility, was completed in 2003, but the station renovations have been put on hold while the city considers various options to redevelop the nearby riverfront.

Brattleboro has retained its artistic flair and is noted for its sizable collection of art galleries, performing arts groups, and artists’ studios. “Gallery Walk” takes place every month, and allows residents and visitors to view the creations of the visual arts and live performance communities. Among the many festivals that take place throughout the year, perhaps the most unique is the “Strolling of the Heifers” each June. To honor the region’s dairy heritage, heifers are dressed in garlands of flowers and paraded up Main Street to the Common for a day long celebration that includes food booths, live entertainment, and demonstrations that emphasize sustainable and healthy lifestyles.

The Vermonter is financed primarily through funds made available by the Vermont Agency of Transportation, the Connecticut Department of Transportation and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation.

Station Building (with waiting room)

Features

- ATM not available

- No elevator

- No payphones

- No Quik-Trak kiosks

- No Restrooms

- Unaccompanied child travel not allowed

- No vending machines

- No WiFi

- Arrive at least 30 minutes prior to departure

Baggage

- Amtrak Express shipping not available

- No checked baggage service

- No checked baggage storage

- Bike boxes not available

- No baggage carts

- Ski bags not available

- No bag storage

- Shipping boxes not available

- No baggage assistance

Parking

- Same-day parking is not available

- Overnight parking is not available

Accessibility

- No payphones

- Accessible platform

- Accessible restrooms

- No accessible ticket office

- Accessible waiting room

- No accessible water fountain

- Same-day, accessible parking is not available

- Overnight, accessible parking is not available

- No high platform

- Wheelchair available

- Wheelchair lift available

Hours

Station Waiting Room Hours

| Mon | 12:00 pm - 02:00 pm 04:00 pm - 06:00 pm |

| Tue | 12:00 pm - 02:00 pm 04:00 pm - 06:00 pm |

| Wed | 12:00 pm - 02:00 pm 04:00 pm - 06:00 pm |

| Thu | 12:00 pm - 02:00 pm 04:00 pm - 06:00 pm |

| Fri | 12:00 pm - 02:00 pm 04:00 pm - 06:00 pm |

| Sat | 12:00 pm - 02:00 pm 04:00 pm - 06:00 pm |

| Sun | 12:00 pm - 02:00 pm 04:00 pm - 06:00 pm |

Amtrak established the Great American Stations Project in 2006 to educate communities on the benefits of redeveloping train stations, offer tools to community leaders to preserve their stations, and provide the appropriate Amtrak resources.

Amtrak established the Great American Stations Project in 2006 to educate communities on the benefits of redeveloping train stations, offer tools to community leaders to preserve their stations, and provide the appropriate Amtrak resources. Amtrak is seizing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to transform rail and Retrain Travel. By modernizing, enhancing and expanding trains, stations and infrastructure, Amtrak is meeting the rising demand for train travel. Amtrak offers unforgettable experiences to more than 500 destinations across 46 states and parts of Canada. Learn more at

Amtrak is seizing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to transform rail and Retrain Travel. By modernizing, enhancing and expanding trains, stations and infrastructure, Amtrak is meeting the rising demand for train travel. Amtrak offers unforgettable experiences to more than 500 destinations across 46 states and parts of Canada. Learn more at